CBDC: The Ultimate Pathway to De-Dollarization

Laila Shaheen

5/19/20256 min read

The concept of CBDCs emerged as a response to the increasing popularity of cryptocurrencies and the growing digitization of financial transactions. At its core, CBDC is simply the digital representation of a sovereign currency that is issued by and is the liability of the central bank.

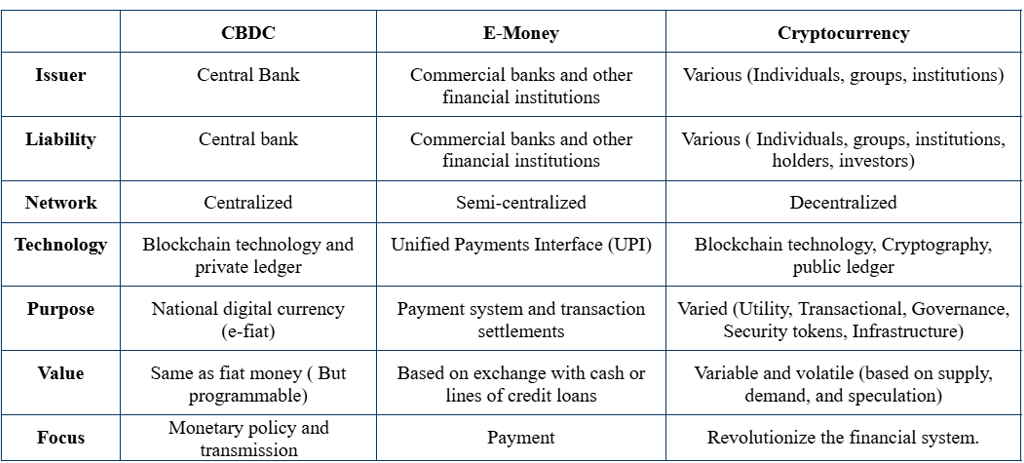

CBDC vs. E-Money, and Cryptocurrency

Unlike electronic money (e-money) or cryptocurrency, CBDC is a legal tender issued and regulated directly by the central bank or government. It is important to differentiate it from other types of digital money to problematize referring to it using terms like “digital money” or “e-money.”

Figure 1: CBDC vs. E-Money vs. Cryptocurrency

As outlined in Figure 1, CBDC, e-money, and cryptocurrency differ in many respects.

Most importantly, a CBDC is the digital representation of a nation’s currency; the government backs it and is centralized.

CBDC is meant to replace or co-exist with a nation’s fiat currency; it is used as a medium of exchange, store of value, and unit of account.

This is an important distinction because the “digital” aspect of CBDC is not what truly makes it revolutionary. Rather, it is the legal, political, and economic power implied by its use as a legal tender.

The term “CBDC” encompasses a variety of digital currency forms, each with its unique characteristics and functionalities.

First, CBDCs can be categorized based on access restrictions into wholesale CBDC (W-CBDC) and retail CBDC (R-CBDC). W-CBDCs are designed primarily for financial institutions, particularly Real-Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) users, such as central banks, commercial banks, and large financial entities.

These CBDCs facilitate interbank settlements, large-value transactions, and cross-border payments. This is the type of CBDC we are interested in for the purposes of this exploration and will be revisited in a following section. In contrast, retail CBDCs are intended for public use, meaning individuals, businesses, and non-financial institutions can access them for everyday transactions.

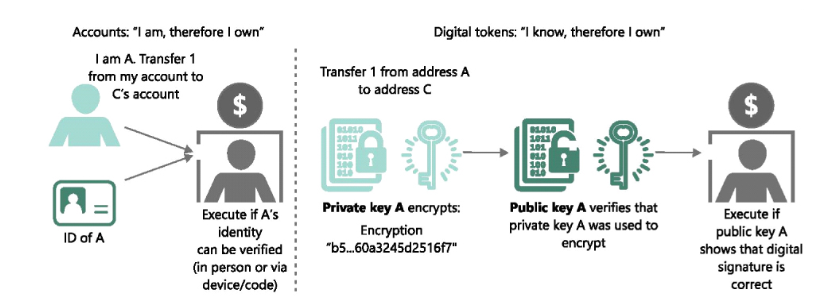

Secondly, CBDCs also differ based on anonymity-based classification into account-based and token-based CBDC. Account-based CBDCs are directly linked to the holder’s identity, requiring users to register with a central authority, such as a central bank or a financial institution. On the other hand, token-based CBDCs offer a higher degree of anonymity, similar to physical cash transactions. Instead of being tied to an individual’s identity, token-based CBDCs are verified using cryptographic methods, allowing users to conduct transactions with minimal oversight.

Figure 2: Account-Based vs. Token-Based CBDC (Auer & Böhme, 2020)

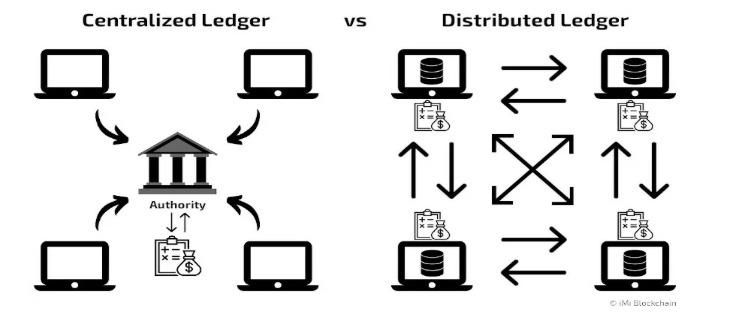

Third, CBDCs can be categorized based on their transfer mechanisms, which determine how transactions are recorded and processed, into centralized and decentralized.

In a centralized CBDC system, transactions are processed using Centralized Ledger Technology (CLT), where a central authority, the central bank, manages and verifies all transactions. This system operates similarly to traditional banking systems, where a single entity oversees payment processing, ensuring security, efficiency, and regulatory control.

Conversely, decentralized CBDCs use Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT), such as blockchain, where transactions are verified across multiple nodes or participants rather than a single central entity. This setup enhances transparency, security, and resilience, as no single party controls the entire system.

However, while there could be less centralization in the transaction settlement of CBDC, the change in the supply of CBDC is still controlled by the central banks.

Figure 3: Centralized Ledger Technology vs Decentralized Ledger Technology (Isler, 2023

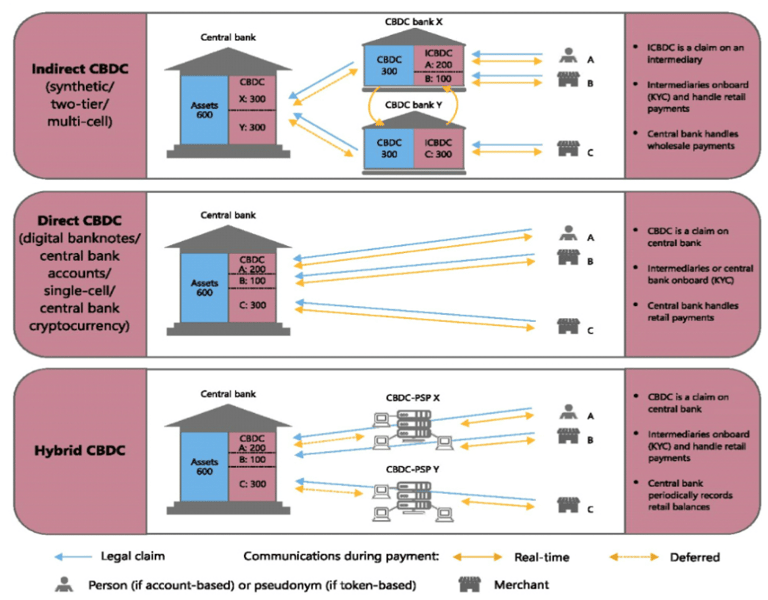

Finally, CBDCs differ in claims and transaction management, with three main models: direct, indirect, and hybrid.

In the direct model, users hold CBDCs directly with the central bank, eliminating the need for intermediary commercial banks.

Conversely, the indirect model relies on private sector intermediaries like commercial banks and payment service providers to manage transactions.

The hybrid model combines both approaches, allowing private entities to process payments while users retain direct claims on the central bank.

Figure 4 illustrates these three types. Direct and hybrid CBDCs are the type of transaction management models this exploration is interested in highlighting. Since de-dollarization requires the elimination of unnecessary intermediaries to enable direct cross-border transactions, direct and hybrid CBDCs offer the technological infrastructure to facilitate this objective.

Figure 4: Direct, Indirect, and Hybrid CBDC (Auer & Böhme, 2020)

Cross-Border Wholesale CBDC (W-CBDC)

The majority of international transactions are settled through a network of correspondent banks, which rely heavily on systems like the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) to facilitate communication between institutions across different countries.

Typically, these transactions are conducted in USD, even when the underlying trade involves other currencies, as the dollar serves as the dominant intermediary for its accessibility and high liquidity.

This process normally involves multiple layers of intermediaries that handle currency conversions and clearances, often leading to increased transaction costs, delays, and reduced transparency.

Beyond de-dollarization, the current system is simply not efficient or secure enough when taking into account the kind of advanced technology we have access to today. For instance, SWIFT, originating from 1970s-era technology, functions solely as a messaging system that directs banks on how to process payments, but it does not directly settle transactions.

Instead, it depends on correspondent banks, creating a multi-tiered process that often involves several intermediaries. As a result, this setup leads to slow processing times, low transparency, and high transaction fees.

Secondly, even if we manage to upgrade SWIFT, the current financial system's reliance on correspondent banking is a key weakness as the number of active Correspondent Banking Relationships (CBRs) globally is in steep decline.

Between 2011 and 2022, the number of CBRs declined by 30%; 4% of which occurred in 2022 alone. This drop has been accompanied by a 61% increase in the total volume of cross-border transactions over the same period.

Driven largely by increasingly complex regulatory requirements, which make compliance significantly more costly for banks, this decline is expected to accelerate as rising geopolitical tensions further fragment the global financial system and complicate compliance, particularly around sanctions screening.

W-CBDC: A Technical Solution to A Geopolitical Problem

W-CBDC shines as an unparalleled solution for overcoming the challenges posed by the decline of CBRs and the increasing weaponization of international financial systems.

Unlike traditional banking, which depends on a series of intermediaries, W-CBDCs allow for direct settlement between central banks, bypassing the traditional correspondent banking system and Western-dominated infrastructure like SWIFT.

This not only reduces transaction costs and speeds up settlement times but also eliminates the need to convert currencies into USD before making international payments. As a result, countries can carry out transactions using their local currencies, improving financial sovereignty and reducing reliance on the USD, all while ensuring faster, safer, and cheaper operations across borders.

For example, consider a trade transaction between South Africa and Brazil.

Under the current system, the two countries would typically have to invoice in USD and convert their local currencies into dollars for settlement.

This means that South Africa, for instance, would convert its rand into U.S. dollars, transfer the payment through a network of correspondent banks, and Brazil would then convert those dollars into reals. This multi-step process introduces extra fees, delays, and complexity due to the involvement of multiple intermediaries.

However, with W-CBDC, South Africa and Brazil could avoid these issues. Instead of invoicing in USD, both countries could settle transactions directly in rand and real.

There are various ways in which CBDCs can facilitate this process depending on the architecture chosen.

One simple approach being as follows: central banks issue their respective currencies on a shared CBDC platform. Participating banks, both local and international, would be able to hold and transact using both local and foreign CBDCs. Local banks could exchange their central bank balances for CBDCs on domestic payment networks. This arrangement would enable different banks to process payments directly with foreign banks using all available CBDCs on the network.

In other words, W-CBDC would facilitate the secure, real-time exchange of these two digital currencies between the central banks, or participating local banks of South Africa and Brazil, without needing to route through a correspondent bank or convert to USD.

This method would not only reduce the transaction time, lower costs, and eliminate the risks of currency fluctuations, it will also bypass the involvement of the U.S.-dominated financial institutions and other correspondent banks that can be easily weaponized.

Now that we understand how W-CBDC could theoretically enable countries to bypass traditional correspondent banking networks and USD-denominated financial infrastructures in their international trade, questions about implementing this in practice are bound to come up. The next chapter highlights the concrete manifestation of this technology in project m-Bridge, the largest multilateral cross-border CBDC project.

© 2025. The PoliTech Brief. All rights reserved.